Guitars are nickel-tongued troublemakers. They’re agents of mischief and masochism, ambassadors of bedroom slackerdom. They demand constant tuning, crackle with cable noise, prefer to be wrung by their necks and slashed across their abdomens. Within each of our lifetimes, it’s likely that we’ll have witnessed dozens of guitars teetering on the edge of total disrepair — an old twelve-string strung out and disemboweled on a flea market table, or a vintage Telecaster rotting in someone’s rec room, paint-chipped and past its prime. They amplify the basest emotional impulses of their performers: anguish, mania, self-obliteration.

More importantly, though, they generate memories. I think of places: Twin Peaks, in San Francisco, where my high school friends and I would bring a couple of guitars and howl into the valley as our voices got sliced up by anarchic ribbons of wind; strolling through the cemetery near campus, playing My Bloody Valentine’s “she found now” on repeat, buried under several inches of arctic fuzz; the dim basement of a punk house in Harrisonburg, VA, where friendly strangers cavorted under canopies of cigarette smoke, circling the remains of a smashed 40oz; listening to Modest Mouse’s Interstate 8 while speeding across the lonesome stretch of the I-5 between Los Angeles and San Francisco, belting the lyrics at the top of my lungs just to keep myself awake; the dozens of bedrooms and practice rooms where I’ve jammed with both friends and strangers — hundreds of hours of wordlessly trying to find each other through music.

Lately, however, they’ve also begun to conjure up vivid memories related to the internet. A lot of my formative experiences related to music — both listening to it and learning how to play it — have taken place online. During the mid-2000s, when I was still in middle school, my love for music made with guitars is what ferried me through the internet’s depths. Though guitars don’t evoke the same things they did in past, pre-online eras of music, they retain both creative utility and cultural significance in the modern age.

But why? Why is it that, with every new generation of music, we extend such boundless compassion to this failson of the chordophone family, an instrument so wretched and accident-prone? Why does it feel like we will never stop needing them?

Take, for example, Chanel Beads’ debut LP Your Day Will Come, one of my favorite albums of the year so far. They’re the kind of artist that first comes into your awareness as an “internet band”; the music video for “Ef,” their breakout hit from 2022, features aesthetic flourishes — stalactitic typefaces and saw-edged 3D models — one might associate with hyperpop artists. But sonically, their songs are more aligned with the strains of Bandcamp bedroom music that have emerged over the past decade, using digital tools to expand the interiority of modest pop song structures.

Guitars feature heavily throughout Your Day Will Come. Pitch-shifted guitars clatter in the periphery of songs like “Embarrassed Dog” and “Unifying Thought,” flanking anthemic melodies with brushstrokes of tonal color. When guitars infused with chorus and digital harmonies first arrive on “Dedicated to the World,” they feel like rays of light penetrating the morning fog. Detuned strings give “Urn” a playful slant, flirting with flat notes and fucked chords without devolving into complete atonality.

In both composition and arrangement, Your Day Will Come reflects the baroque sensibilities of ‘80s bands like Prefab Sprout, Scritti Politti, or The Blue Nile, in which guitars rub shoulders with violins and woodwinds and synths dripping with FM modulation. It’s an approach to production that recalls recent releases by artists like ML Buch and Westerman: rich sonic environments in which guitars stop sounding like guitars, instead providing impressionistic textures that dance around a central chord progression.

But when I saw Chanel Beads live at a house show a month or so ago, I was struck by how different the music felt in person. As Chanel Beads’ Shane Lavers and Maya McGrory belted melodies in unison over nothing but a guitar, an electric violin, and a backing track, I wasn’t thinking of ‘80s sophistipop; instead, the scene reminded me of a live performance of Alex G’s “Mis” I’d watched on YouTube years ago.

Silly as it sounds, I genuinely believe the very presence of a guitar is enough to inject a live performance with the energy of a boisterous house show — it’s enough to convince you that the music you’re hearing is in the process of saving your life. It’s enough to rouse you to sing along with the crowd, even if you forget part of the lyrics or sound way out of tune. Months or years of private listening, sequestered to bedrooms or car stereos or headphones, culminate in a single moment of communal catharsis. That’s the feeling I got when I watched that YouTube video of Alex G, and it’s the same feeling I got from the crowd at the Chanel Beads show.

In a post-MIDI, post-Ableton, post-Splice world, it becomes harder to distinguish between the real and the synthetic. Nowadays, random number generators can introduce “lifelike” entropy to digital instruments, introducing aberrations in velocity, rhythm, and pitch. Conversely, advancements in audio effects and processing techniques have given guitarists access to otherworldly palettes of sound that would have been unthinkable to the musicians of yore. (Look no further than Rachika Nayar’s Heaven Come Crashing or the work of Tera Melos’ Nick Reinhart for examples of how far guitar processing has come.)

Sample libraries have grown to encompass nearly every acoustic instrument imaginable, empowering bedroom producers with the ability to conduct virtual orchestras using only a laptop. YouTube tutorials and file-sharing services have democratized the tools and knowledge that used to belong solely to industry professionals. The ability to construct an esoteric soundscape has become less and less tethered to specific pieces of gear or time spent in a professional studio.

You can see this play out at DIY shows nowadays, where it feels like arrangements have become more eclectic than ever. I’ve been seeing more and more vocalists using the same TC Helicon auto-tune pedal that stadium-worthy pop stars use, only re-appropriated for indie rock or folk or shoegaze. Conversely, it feels more and more common for laptop- and sampler-based musicians to combine fat 808s with abrupt punk- or heavy metal-inspired breaks, swerving from synths to guitars as an abrupt transition.

Guitars used to be evoked in acts of rebellion against movements in popular music, pushing back against then-emergent genres like disco or synth-pop. But in this landscape, it’s easy to wonder: What do guitars offer in the present, decades after rock and punk and grunge?

This question has been on my mind ever since I noticed guitars springing up in various corners of the ever-splintering hyperpop movement. PC Music label head A.G. Cook released Britpop in May, and — just as with his 2020 opus 7G — there’s an entire disc dedicated to the record’s guitar-forward tracks. True to Cook’s style, Britpop’s guitars manifest as both glittery harmonics and crunchy power chord stabs, reflecting the dichotomy between tenderness and harshness that pervades his work as a producer.

Last year, Cook teamed up with veteran PC Music producer Finn Keane (aka EASYFUN) to release Soft Rock, the duo’s first official album under the Thy Slaughter moniker. When they took the stage to perform their “debut” show as a part of a PC Music farewell event here in LA, they weren’t using DJ controllers or laptops; instead, they had guitars strapped around their necks, Keane on lead and Cook on bass. Across 2023, Keane also released a duo of EPs, Acoustic and Electric, that live up to their titles.

It’s not just them — guitars have been all over internet music lately. Yung Lean and Bladee’s Psykos, released back in March, is a record replete with guitars, building songs around lethargic post-punk arpeggios swimming in reverb. glaive, one of 2020’s breakout “digicore” stars, has spent the past few years drifting from up-tempo anthems with blown-out 808s to confessional ballads with acoustic guitars. Since 2019, artists like 100 Gecs, underscores, and Jane Remover have expanded on the heterogeny of PC Music’s proto-hyperpop foundations, introducing elements of pop-punk and third-wave emo to club music collages — often in the form of distorted guitars. The music video for underscores’ “spoiled little brat” demonstrated that it wasn’t too far-fetched to imagine a conventional band making this music.

One of the records that most surprised me, however, is Quadeca’s SCRAPYARD. It’s a mixtape that was released in February as the culmination of a series of EPs Quadeca had put out across the latter part of 2023 — though I didn’t know that when I discovered it earlier this year.

Part of the reason I hadn’t heard of Quadeca before is that he originally made a name for himself as a YouTuber. He got his start posting compilations of FIFA packs (FIFA’s incarnation of the lootbox demon that plagues every game-as-service content spiral) way back in 2012, when he was only eleven years old. He pivoted to rap in 2014, and his breakout single was a song called “Wii Music Fire” that features a noticeably low-effort flip of the iconic “Mii Channel” theme. By 2018, he shared headlines with influencers like Logan Paul and KSI, men who broadly belong to the “manosphere lite” side of e-celebrity.

I’ve always had low expectations for music produced by people who are most well-known in the streaming and content creation spheres — especially people who make their debut as rappers. Maybe I’ve been exposed to too much of vtuber Mori Calliope’s music, or maybe it’s that I’ve seen too many music videos for electro-swing songs inspired by video game characters.

Either way, the “music-as-content” continuum is something that tends to skeeve me out. Capitalistic forces have incentivized producers to turn tutorial channels into content mills; nowadays, hardware reviews and sponsored segments bookend educational material that used to be offered for free, usually by someone filming their monitor with their phone. SEO best practices dictate that you have to use titles like “How to Kaytranada” to attract viewers, flattening artists and their respective “sounds” into a set of replicable characteristics.

This attitude towards music abets shitposting more than it encourages creative conversation. Drain Gang, the only “boy band” to whom I’ve ever sworn allegiance, have become a metonym for a “hyper-online” aesthetic defined by gender-bent outfits, Evangelion title cards, and cryptic allusions to Catholic imagery. As a cultural node, they’ve somehow become proximal to both Serial Experiments Lain and Roblox. Their reputation precedes their work.

As a result, it normally wouldn’t occur to me to check in on an artist whose first hit was “Wii Music Fire.” But SCRAPYARD makes a strong case for Quadeca’s maturation as an artist, bringing a coherent shape to the eclectic range of influences that have informed his unique voice.

Guitars play a heavy role in imbuing songs with emotional color, especially in the record’s first half. Listen to the aching, tone-bent guitars that open “PRETTY PRIVILEGE.” Guitars unfurl again as the first verse kicks in — modified power chords and major-seventh ennui, hallmarks of the Bandcamp bedroom pop zeitgeist. “A LA CARTE” is full of treble-forward Midwestern emo twang, a fitting accompaniment for the juvenile melodrama of lyrics like “You can have my tongue, just promise you’ll take it a la carte.” On “DUSTCUTTER,” lovesick, open-stringed chords are buried by thick 808s, achieving dream pop lucidity without compromising on its kick-driven momentum.

I won’t lie — at its worst, Quad’s delivery reminds me of Bright Eyes’ Conor Oberst or Hobo Johnson, veering a little too close towards the mawkishness of bathroom graffiti or slam poetry. But the guitars redeem him; his ambition as both a songwriter and producer is so palpable that I can forgive him for getting a little puerile from time to time.

In my opinion, one of the most useful metrics for determining a musician’s cultural impact is seeing if people have posted tablature of their music to ultimate-guitar.com. You can find Quadeca there, for example, with twenty-six tabs to his name.

I’ve always been a staunch devotee of tablature, which is a method for notating guitar parts that doesn’t rely on any formal knowledge of theory. Standard notation involves marking things like pitch and duration with precision, using musical staves that indicate each note’s relationship to a scale or key. Tablature, on the other hand, is designed to notate the physical placement of fingers on the fretboard, representing individual notes as numbers that correspond to frets.

Technical as they may be, these details can have significant repercussions on how a guitarist develops their voice. Even if they don’t know how to read sheet music, a guitarist can learn scales and chord progressions through experimentation; they can visualize chords as sets of numbers or physical “shapes” on the fretboard without absorbing a single sentence of chord theory. You can write songs simply by dragging a single shape — a power chord with two fingers on two frets — up and down the fretboard, and you could do this with a guitar that only has two working strings. (Just look at the beaten-up five-stringed guitar featured in this music video for Guided By Voices’ “I Am a Scientist.”)

One of the best things the internet has ever encouraged is the Samaritan impulse to reverse-engineer tablature and share it with others. In addition to being an educational resource, a piece of tablature — usually shortened to “tab” — can grant a guitarist a deeper level of intimacy with a song they love. This is how you feed the forlorn, bedroom-bound guitarists languishing in insecurity: you teach them how to fish.

Growing up, sites like ultimate-guitar.com felt like reservoirs of teenage loneliness. It’s easy to get lost drifting across its snowbanks of monospaced tablature. The site might have “official” tabs authored by a team of guitarists today, but back in the 2000s, no knowledge was sacred; the most highly rated tab for a song might have been the least faithful to the recording. You’d wade into the Modest Mouse section and find ten different versions of “Dramamine,” each one authored by a person with a different take on fingerings and voicings.

Authoring tabs is an interpretive art, and inaccuracies are a given, especially without the guardrails of standard notation. Most of these authors are amateurs, often devising their own ways to describe chords and picking patterns. Some include URLs to videos that feature live performances where the guitarist’s hands are briefly visible. Learning a song through someone else’s tab can feel like a spiritual act; you’re both chasing the specter of the song you hear in your heads, but asynchronously, hoping to find middle ground.

The fact that people have posted tabs for Quadeca’s music to ultimate-guitar.com proves to me that somewhere, some kid is learning how to play a B7 by performing “DUSTCUTTER” for themselves in their bedroom. Maybe they’re learning jazz voicings from the dulcet, acoustic arpeggios in “EASIER.” I’m hard-pressed to come up with a more meaningful achievement when it comes to songwriting.

This was more or less how I learned to play and eventually write music: via webpage upon webpage of digits and dashes typed in Courier, slowly etching themselves into the grooves of my brain.

One of my most-frequented educational resources was The Sonic Youth Tablature Archive, a fansite that collects charts for every single song the band has ever performed. The site catalogs each of the 86 non-standard tunings they’ve used across their discography, illustrating that it takes more than a pedalboard and a tube amp to achieve their sound; it also takes reckless imaginative thinking. Inspired, I started committing my own sacrilege, filling notebooks with tabs written in blasphemous tunings where four strings are tuned to the same note.

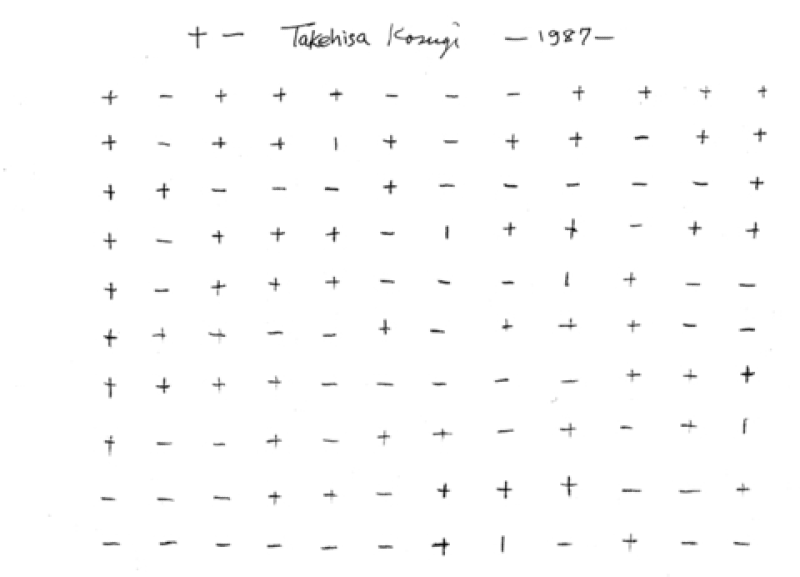

That’s also where I learned about graphic scoring, an experimental method for notating music that can range from written instructions to abstract illustrations. I was captivated by the elegant understatement of the chart for “+ -,” a composition by the Fluxus composer Takehisa Kosugi that the band performed as a part of their avant-garde SYR series. I’d never even touched a bass, but I still spent hours poring through Kim Gordon’s bass parts, studying her methods for achieving thundering low-end sludge. I wedged drumsticks and glass bottles in between the strings and the fretboard to emulate Thurston Moore’s no-wave theatrics.

Sites like this were common when the internet was less centralized. I also used to visit Slay Tracks and to here knows web, which are blogs dedicated to chronicling tabs for Pavement and My Bloody Valentine, respectively. These were passion projects by listeners who treated their work like prophetic intercession, scouring old interviews and footage of live performances in search of teachings that could inform the tablature. Studying tabs heightened my appreciation of the music: the sardonic lilt in Stephen Malkmus’ off-kilter solos, the ghostly melodies marbled throughout My Bloody Valentine’s “When You Sleep.”

One of the tabs I consulted often was for Women’s “Shaking Hand.” It was posted in 2009 to a blogspot maintained by someone named Kris Ellestad, who mostly wrote tabs for songs by the Dirty Projectors. Compared to the amateur scribblings scattered across ultimate-guitar.com (and I mean that affectionately), Ellestad’s tabs are works of art in and of themselves. The tab for “Shaking Hand” — which, fifteen years later, is still accessible here — is both tidy and comprehensive, including timestamps, subdivisions, and proper notation for tremolo picking.

Over just two albums — 2008’s Women and 2010’s Public Strain — Women deepened my love for music made with guitars. When I first heard them, they reminded me of Dirty-era Sonic Youth, which is around when they began channeling their experimental sensibilities into sweeter melodies and cleaner tones. Women’s songs house spiderwebs of interlocking guitar parts and rhythmic patterns, but woven with a tenderness that’s often absent in music with such jagged edges. Even today, the final forty seconds of “Shaking Hand” constitute one of the most beautiful passages of music I’ve ever heard. I'd watch this live performance of the song religiously.

Ellestad never ended up posting other tabs for Women’s music, so I learned “Locust Valley” and “Eyesore” on my own. I learned how to use a tremolo effect to achieve the shimmering texture that comes in right before the second verse in “Black Rice”; I learned how to emulate the bratty gnashing sound in the intro to “Drag Open” by scraping a pick across the strings, above the bridge and away from the pickup. When I started playing music with other people in college, I was surprised at how many other guitarists had consulted the same tab for “Shaking Hand” at some point in high school.

It wasn’t until I listened to Diamond Jubilee that I realized how much Patrick Flegel — Women’s singer and one of its guitarists — had taught me. It’s Flegel’s seventh full-length release under the Cindy Lee moniker, a double-LP that garnered glowing reviews from publications like Pitchfork and Paste upon its release in March.

It felt right that it was released on a Geocities blog, in a corner of the internet you had to work to find. It reminded me of how Deerhunter’s Bradford Cox used to release Atlas Sound mixtapes to Mediafire, squirreling music away where it’d be less vulnerable to the whims of the music industry. But it’s also more than just an act of defiance; it’s an insistence that the listener sit with the music in isolation, outside of an infinite scroll.

Nothing on Diamond Jubilee matches the urgency or density of Women’s music. On the contrary, its songs often linger in more sentimental moods, taking their time to summon phantasms of genres past. It’s refreshing to hear Flegel’s playing applied to different contexts, filling caverns of Phil Spector-grade reverb and rambling across classic rock ballads. Songs like “Golden Microphone” and “Kingdom Come” are confirmation that Flegel was at least partly responsible for the elements of bright sunshine pop that pervaded Women’s music.

The record’s hypnagogic atmosphere is owed, in large part, to Flegel’s approach to both playing and recording guitar parts. Throughout, Flegel’s guitar playing is at once virtuosic and messy, allowing strings to slip out of tune or notes to go partially fretted. You can practically hear their foot rocking the wah pedal back and forth in the intro to “Flesh and Blood," a quivering rhythm that drives the song forward. It’s a perfect complement to the record’s haunted atmosphere, evoking a tempered sense of mischief.

It’s remarkable how much sonic territory Flegel is able to cover with such a modest palette of sounds, most of which come from guitars. Guitars define the pulse of each song, the steady heartbeat around which soundscapes form. They keep the rhythm, deliver solos, populate chord progressions with fastidious arpeggios and loquacious counter-melodies. Most of the time, they’re front and center; in other instances, they sound distant, as if emitting from an ancient amp a few doors over. Synths, bowed instruments, and even drums often feel like auxiliary embellishments, emerging only to furnish moments of grandiosity.

Guitars, by nature, encourage you to abandon conventional wisdom. Guitarists originally invented distortion by attacking amplifiers with sharp objects, poking holes into speaker cones to produce gnarly, fickle sounds. There’s also the simple whammy bar, which My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields extended to create his signature “gliding” effect, transmuting chords into shape-shifting apparitions. From Jimi Hendrix to Wes Montgomery to B.B. King, legendary guitarists from across genres have proven to be resourceful auto-didacts, pioneers of their own technique. Guitars are instruments that beg to be played “wrongly,” a quality that makes them effective in emphasizing the most nuanced and idiosyncratic elements of a performer’s style.

Diamond Jubilee is evidence that Flegel is a guitarist who’s intimately familiar with their instrument. The LP’s lo-fi recording environment bakes the quirks of Flegel’s playing into the music, warts and all. It’s less about capturing the perfect take than it is about bottling the electric energy of that first take — the feeling of sharing a room with Flegel as they idly pick through talkative riffs. It’s like hearing the gentle click of a stop button during a song recorded to a four-track cassette machine; it’s proof of life, evidence that someone’s on the other end.

This, above anything, is what guitars do best: They ground listeners in a sense of “place,” gesturing not only to the presence of a human performer but the context that surrounds them. They recall every single other instance you’ve heard or seen or played a guitar before, stacking memories on top of each other like multiple exposures on a single piece of film. Whether it’s cassette machine hiss or the hum of a Marshall stack, guitars allow the nuances of the recording environment to intrude into the world of the song — even if that environment is someone’s bedroom.

This is ultimately why I don’t think they’ll ever go away, even in music that lives primarily on the internet. They’re sensitive creatures — they buzz with ravenous anticipation, squeal at the gentlest touch, and make every error a spectacle. They have a unique capacity to convey feelings of loneliness: the geriatric blues rocker shredding on the showroom floor of a Guitar Center, or the teenager strumming an unplugged Stratocaster on their bed, recording a voice memo on their phone. But that’s what makes them so effective as anchors to the material world, encouraging intimacy between performers and listeners.

I hope people never stop posting tabs. I hope The Sonic Youth Tablature Archive will still be posting “Songs of the Week” even when my bones are brittle. I hope guitars will continue to haunt the internet decades into the future.

However, something tells me I won’t have anything to worry about. Year after year, I pray silently for fields of fuzz and twang, and I’ve yet to be disappointed.

P.S.: There were a lot of 2024 records I didn't have the space to mention in this piece. To compensate, here's a mixtape comprised of choice cuts from across the year's range of guitar music: